Parenting a teenager is hard! And it’s even more so for Amber and Jason Lesovoy, parents to Jaymes (14), Sierra (12) and Jessica (3). That’s because, for the past four years, their teenage son has lived outside of their North Carolina home – first in therapeutic foster care and, presently, in a residential program (often called group home). “Our goal is to make the world around Jaymes accessible to him, and to accommodate his needs as much as possible,” Amber proclaims.

As an infant, Jaymes seemed “chronically hyperactive and agitated, and very hard to soothe. He was delayed in speech and language, as well as physically,” the stay-at-home mom recalls. At age 2, he was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Tourette syndrome, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and mood dysregulation disorder. Numerous therapies were employed, such as speech, occupational, physical, equestrian and others. But, unfortunately, “the situation at home had become so volatile that neither Jaymes nor the other children were safe,” Amber shares, adding, “We reached a point where he was determined to hurt himself and his sisters. He would hide weapons, like kitchen knives, in his room to attack the girls with after everyone went to sleep. ”Amber and Jason tried to “Jaymes-proof” the house by using locks and hiding potential weapons, but Jaymes would find ways to generate threat. Also alarming, Jaymes fabricated abuse allegations which led to unwarranted investigations by child protective services – a devastating blow to the loving parents.

The couple finally chose a “last resort” option of residential treatment care – something that Amber describes as both a heart-wrenching decision and a relief. Jaymes spent about a year at New Hope Treatment Center in South Carolina in a specialized dual diagnoses unit for boys with autism and mental illness. There, Amber says, “he developed new coping skills and learned patience, and his violent behavior stopped.”

The Lesovoy’s experience is actually shared by many. In 2015, according to Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 271,000 children ages 12 to 17 received care for mental illness at a residential treatment facility. National Alliance on Mental Illness data shows that half of all chronic mental illness begins by age 14, and 13 percent of American children ages 8 to 15 will experience a severe mental disorder. The Washington Post recently reported that, according to the Child Mind Institute, more children in the U.S. have a psychiatric disorder than cancer, diabetes and AIDS combined; and, for the most severely affected, residential treatment is the best way to ensure their safety and help them stay out of the juvenile justice system.

After succeeding at New Hope, Jaymes transitioned to Evans-Blount Total Access Care in Burlington, N.C. – just about an hour from the Lesovoy’s home in Kernersville – where he resides with four other boys and a dedicated 24-hour staff. Sadly, the Lesovoy’s have faced unfair judgment by others who don’t understand the necessity of residential programs.

“Many parents see Jaymes’ living situation and think we are heartless people who have dumped our kid on someone else to make our lives easier,” describes Amber, and she offers clarification: “Residential treatment isn’t a bad thing. It’s not abandoning your kid. Sometimes it’s the only way to keep everybody safe and happy.”

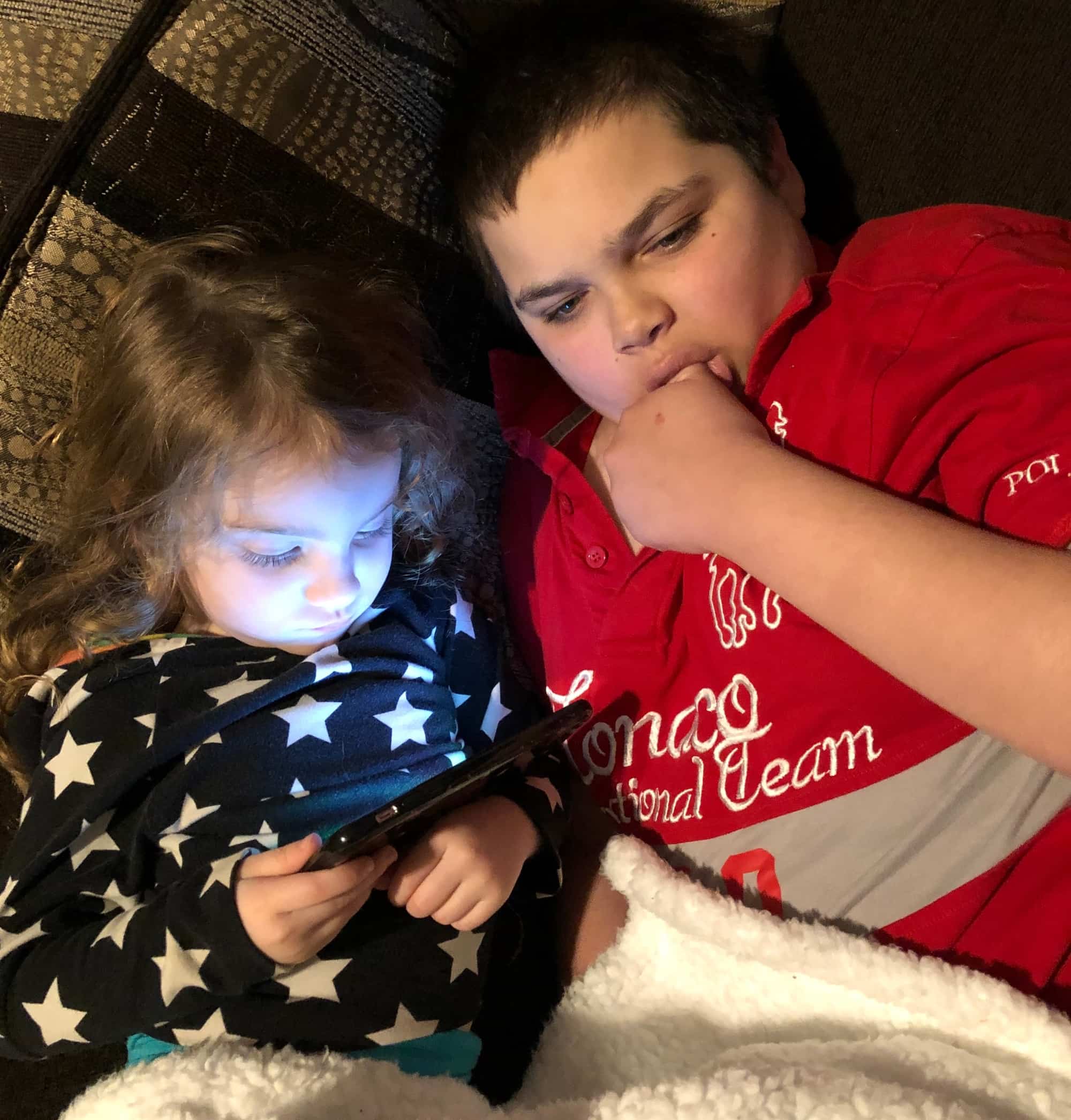

Still, the perception of appropriate care for mental illness remains skewed in comparison to children with physical ailments. For example, people comprehend that a pediatric cancer patient may stay at a treatment facility for care, but don’t translate that understanding to facilities focused on mental illness. Yet for some families, like the Lesovoy’s, residential care is the best option and has proven to be successful. Jaymes is now much happier and making positive strides. He enjoys ‘typical’ kid things, like the iPad and TV (his favorite characters are SpongeBob Square Pants and Scooby Doo); and he loves animals, especially horses and sea creatures.

Pictured: Jessica and Jaymes

Even though Jaymes is no longer under their roof, Amber and Jason assert they’re still the decision-makers for their son’s needs and upbringing, and that’s made possible because of their close involvement with program staff. “We parent him the same as the girls. He has the same rules and expectations as they do when he is at home or out with us. We accommodate his needs, and we do things differently at times to make it work for Jaymes but we’re pretty strict as far as behavior goes,” Amber says. And, thankfully, the sibling dynamic has improved. “Being separated from his sisters while he worked on his behavioral issues and learned to handle his triggers without violence was helpful. We were able to have them interact in safe, controlled settings that gave Jaymes a chance to interact successfully,” Amber shares, crediting the establishment of routines which work in both the residential and family setting.

Jason believes that residential programs are not the first or best choice for all. In fact, he works for a children’s mental health agency where home-based therapy programs are preferred. “From a professional standpoint, the entire grounding and focus of what we do is essentially to keep families intact and children in the home. Clinically, our number one objective is to avoid residential treatment and any disruption to the family dynamic. However, with that being said, we understand the need to escalate the clinical oversight of a child like Jaymes when there is a direct need for it in terms of safety for the individual and family,” he explains. “In the case of Jaymes, while we wish it had not come to residential treatment, ultimately it ended up being the best case scenario for our family and for Jaymes. Removing Jaymes from the home was the only way to keep everyone safe while his medications and therapies are worked out and he learns how to function in the world. It also allows for new and varied perspectives of the situation.”

Jason isn’t the only one with a two-fold understanding. Ten years after her son was diagnosed, Amber learned she also has ASD. “My psychiatrist of ten years diagnosed me several years ago and it was a total surprise to me,” she confesses. She thinks it was missed in her childhood because less was known about autism. In hindsight, she now understands why she’s felt different and struggled with some circumstances. “In a way, I’m very grateful for my autism diagnosis. I feel like it helps me make the right decisions for Jaymes and it gives me a better perspective on things. I know how he will react to certain situations because I know how I react to those situations and I can make his life a little easier by anticipating where he might have issues,” she says. “I like being part of the autism community; we are a supportive, loving tribe.”

Pictured: Amber exploring equestrian therapy.

Amber admits not having her son at home has often left her family feeling broken and incomplete. But, thanks to his progress through residential care, Jaymes is now ready for overnight stays with the family! “We love our son and we wouldn’t change a thing about him. He’s not sick, he’s not broken… he’s simply different. We’re still learning how best to support him so he can get through life successfully and have the same quality of life his peers do,” she says, offering that, “Autism doesn’t need curing, society needs to change and become more tolerant. Kids like Jaymes, and adults like me, need support from the rest of the world. We need the world to understand that small talk is hard and physical touch can be literally painful to us. We need society to accept that we see and experience the world differently than they do, and we don’t need to be fixed. We just need society to work with us.”

Regarding cost of care, Amber relies on private insurance for her own needs but is grateful that Jaymes has access to Medicaid. “He takes many medications, goes to therapy and requires psychiatry and case management services. Our family could not even begin to meet his needs without Medicaid,” she says. The Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA) and the Department of Children and Families (DCF) typically oversee licensing for centers. For more information on residential care, visit your state department of health website or the National Alliance on Mental Illness (nami.org), the nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization dedicated to building better lives for the millions of Americans affected by mental illness.